Missouri Pacific in San Antonio, Page 2

Additional Information and Photos Page

By Hugh Hemphill, author of "San Antonio On Wheels"

and "The Railroads of San Antonio and South Central Texas."

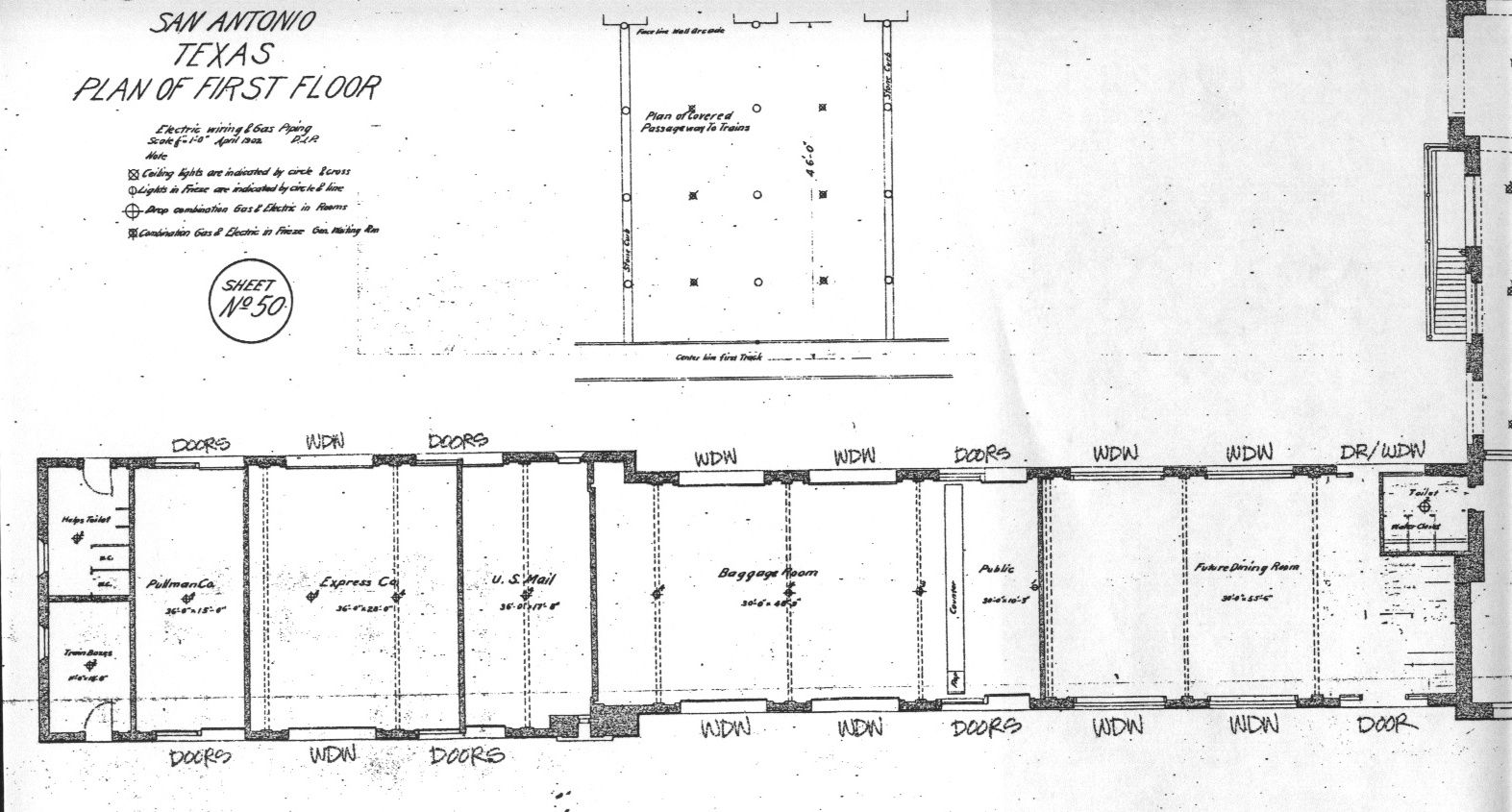

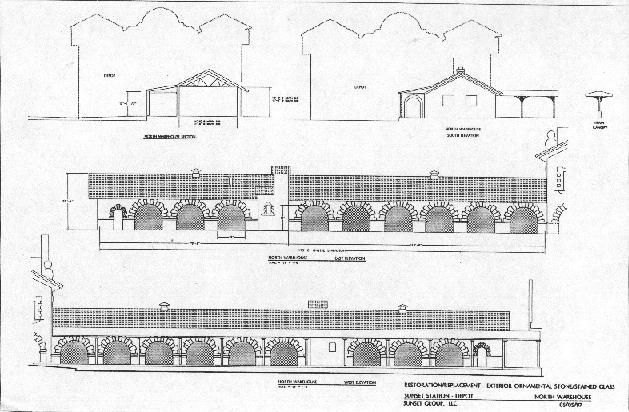

Missouri Pacific Station in San Antonio, 1971

In 2006, an intriguing folder was located at the Texas Transportation Museum detailing an abortive effort on the part of the museum to acquire in 1971 the recently shuttered Missouri Pacific station at the corner of Commerce and Medina Streets. Included in the copious but ultimately fruitless correspondence, which includes letters to and from MOPAC, the San Antonio mayor, the San Antonio Conservation Society, and even US Representative Henry B. Gonzalez, were a number of tiny photographs and an undated area map detail showing the location of many forgotten aspects of MOPAC's operations in downtown San Antonio.

Modern technology has allowed for a generous enlargement of the photographs. Included are some extremely rare images of the baggage room and REA offices located immediately behind the station. More searching just might reveal images of the freight house and the turntable on the other side of the tracks; now we know what to look for.

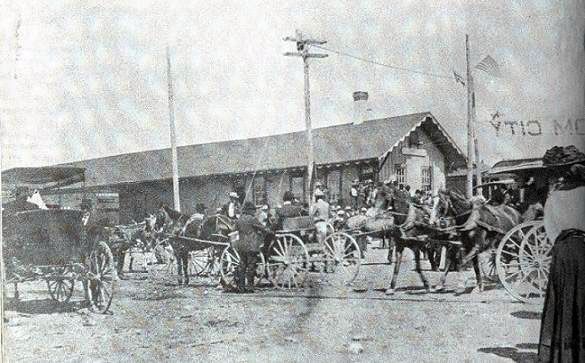

International and Great Northern Hotel in San Antonio

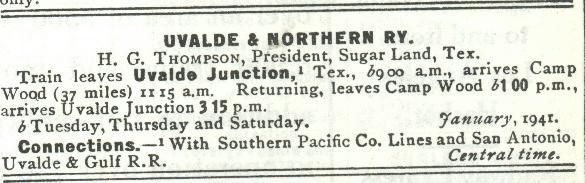

The Uvalde and Northern Railway Company was chartered on March 14, 1914, with the objective of constructing a railroad from Uvalde to a site near Camp Wood Creek in Real County. Investors in the Uvalde and Northern areas purchased or secured options on 50,000 acres of land bearing stands of cedar. Construction work began on May 29, 1914. About eleven miles of grade had been completed by fifty crews when the project was suspended to allow the acquisition of additional right-of-way. The beginning of World War I created further delays. Meanwhile, a 1916 fire consumed thousands of acres of cedar in the Camp Wood Creek cedar brake. The Uvalde and Northern Railway Company was reincorporated on May 11, 1920, due to fears that deferment of construction might have voided the railroad's original charter. With financing by Harry H. Rogers of San Antonio, the town site of Camp Wood was platted by W. A. Thompson, and 37.1 miles of rail reached their terminus there prior to the first train run on Saturday, March 19, 1921. The Uvalde & Northern, unlike the typical tram line used in logging operations, was a common carrier (Class III) offering passenger service and regular freight shipments. A planned eight-mile tramway from Camp Wood to a cedar brake seems never to have materialized.

Camp Wood became a boomtown on a modest scale. Over one hundred cutters and haulers began working for the Uvalde Cedar Company in 1921, most living in a tent city. The first area to be harvested for cedar was the Lost Creek brake west of Camp Wood in Edwards County. In 1924, at the peak of activity, 1342 carloads of cedar posts and other wood products were shipped out, and there may have been in excess of two hundred cedar choppers at work in the brakes near the town. During the late 1920s, according to Uvalde Cedar Company shipping clerk George C. Swint, three trains per week hauled loads of as much as 40,000 posts each from the area. In 1928, 852 railroad cars of timber valued at about $500,000 rolled out of Camp Wood. By 1929, the Uvalde Cedar Company, headquartered in Camp Wood, was said to be the largest cedar shipper in the United States, and business activity generally was quite high. New cars and fine houses were seen everywhere in Camp Wood.

This rosy picture obscured a number of underlying problems. The kaolin deposits were too far from eastern markets to make mining and shipping them profitable. Prices for cedar posts dropped following the introduction of posts made of iron, steel, and treated pine. Most sheep and goat ranches were fenced by 1930, reducing the demand for cedar posts in Texas. Wool and mohair began moving by truck instead of rail. The onset of the Great Depression in October 1929 changed the whole economic landscape profoundly. Passenger service on the Uvalde and Northern ended in 1932. In cities such as San Antonio and Austin, natural gas for heating and cooking began to replace fuel wood, a significant part of Uvalde & Northern's freight tonnage. No shipments of fuel wood occurred after 1935. Though the Uvalde & Northern limped along for several years, carrying petroleum products and enduring a number of washouts, it was running a deficit in most of its later years.

The railroad's most potent foe, however, may have been ecological change. J. E. Robbins, owner of a tourist court and resident of Camp Wood since 1923, lamented that "For twenty years cedar furnished this town with a good-sized payroll, but it's all gone now...." This report was confirmed by another Camp Wood resident, Albert Griffin Wells, who stated that the cedar had been clear-cut within a radius of fifteen to twenty miles around the towns of Camp Wood and Vance. The equivalent of 7,543,297 cedar posts had been harvested. In the process, some 37,716 acres of land were denuded of cedar. After 1940, cedar cutting was only a minor industry in Real County. No rail shipments of cedar were made in 1941, and the Uvalde & Northern's last run to Uvalde was made on August 8 of that year. The tracks were removed by Y. O. Coleman and Jim McKinnery beginning prior to August 22, starting at Camp Wood and working south.

The apparent deforestation of the region surrounding Camp Wood deserves further comment. During the first eight years of the Uvalde & Northern's operation, more than 76 percent of the cedar timber shipped by the railroad was cut. Peak wood harvest (and, considering the uncertainties involved in estimates, perhaps post-harvest as well) occurred in 1924, and the downward trend beginning in 1925 was only exacerbated by the Depression. It appears likely that deforestation was the ultimate cause of the decline in the timber industry in the Nueces Canyon, though it interacted with other factors including lower demand, lower prices, and a greater hauling distance to the railhead. A similar example is the Cedar Tap Railway in Lampasas and San Saba counties, Texas, a line that is also almost totally dependent on the cedar harvest for its existence. Though no data are available on quantities shipped by the Cedar Tap, the life span of this tram railway was less than eight years (1912–1920), apparently due to the depletion of the cedar timber resource.

Assuming a cutting radius of fifteen miles, the Uvalde & Northern drew on an area of 452,390 acres. If twenty percent of that area was occupied by cedar woodland, then there would have been 90,478 acres of woodland available to be harvested. The calculated amount of deforestation indicates that 42 percent of the latter was deforested between 1921 and 1940, inclusive. If the cutting radius were less than fifteen miles, this percentage would be higher. The actual acreage harvested implies a minimum cutting circle with a radius of about 7.7 miles. In any case, the timber near Camp Wood must have been exhausted.

The calculation of deforested acreage does not include known quantities of fuel wood shipped by the railroad, posts and fuel wood cut by ranches and other businesses not associated with the railroad, or deforestation due to fire. Post-harvest on ranches and farms in 1929 alone totaled 316,859 units in the four counties (Edwards, Kinney, Real, and Uvalde) at or near the terminus of the Uvalde and Northern.

Other natural resources in the Nueces Canyon were likely affected by the rapid loss of woodland. Soil loss and the reduction of golden-cheeked warbler habitat are often associated with deforestation in the Edwards Plateau. Though no attempt was made to quantify such effects on the Nueces watershed due to the Uvalde & Northern and associated businesses, further analysis of historic ecological change on the southern fringe of the Edwards Plateau during the twentieth century seems possible.

Postscript: The author also found these pieces of information during his research:

Oak ties were locally cut for the Uvalde and Northern, and 8–12 ties could be sawed from a single tree. At a rate of 2,640 ties per mile and 8–12 ties per tree, it would have required 8,162-12,243 trees to construct the Uvalde and Northern tracks. (37.1 miles) Ties had to be replaced every 7 years on average.

The Uvalde Cedar Company sold ninety different types of lumber and posts, ranging from large saw logs to small fence staves. The largest quantities were of four-inch-wide fence posts, railroad ties, and 6" X 6" and 4" X 4" timbers. At one point, logs were even shipped to the Faber Pencil Company in Germany. The company investigated the feasibility of using cedar from the Edwards Plateau for manufacturing its pencils but found that the wood was too hard for the purpose. Kinds of wood products (posts vs. fuel wood) were not distinguished by the Annual Report of the Uvalde & Northern Railway from 1921 to 1927. During 1928–1935, 33.1 percent of the carloads were fuel wood.

Sources:

William L. Bray, The Timber of the Edwards Plateau of Texas: Its Relation to Climate, Water Supply, and Soil, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Forestry, Bulletin no. 49 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904)

J. H. Foster, "The Spread of Timbered Areas in Central Texas," Journal of Forestry, XV, No. 4 (1917)

A. W. Spaight, The Resources, Soil, and Climate of Texas (Galveston: A. H. Belo and Company, 1882)

Frank J. Nixon, Bandera City (rev. ed., San Antonio: Eighth Corps Area Engineer Reproduction Plant, 1927)

Historic USGS/Military Map Collection, Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Ruben E. Ochoa, "Uvalde and Northern Railway," in The New Handbook of Texas (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1996)

Grace Lorene Lewis, "A History of Real County, Texas" (M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1956)

Allan D. Stovall, Nueces Headwater Country: A Regional History (San Antonio: Naylor Company, 1959)

Uvalde Leader-News, Mar. 25, 1921

L. J. Dean, "Camp Wood, Texas," in Wagons Ho!: A History of Real County, Ed. Marjorie Kellner (Dallas: Curtis Media, 1995)

L. J. Dean, "Uvalde and Northern Railway," in Wagons Ho!: A History of Real County, ed. Marjorie Kellner (Dallas: Curtis Media, 1995)

Sherry H. Olson, The Depletion Myth: A History of Railroad Use of Timber (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971)

Annual reports of the Uvalde & Northern Railway Co. to the Railroad Commission of the State of Texas for the years 1921–1941

Donald L. Huss, "Factors Influencing Plant Succession Following Fire in Ashe Juniper Woodland Types in Real County, Texas" (M.S. thesis, Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, 1954)

David D. Diamond, Gareth A. Rowell, and Dean P. Keddy-Hector, "Conservation of Ashe Juniper (Juniperus ashei Buchholz) Woodlands of the Central Texas Hill Country," Natural Areas Journal, XV, No. 2 (1995)

Leona Gray, "The Uvalde and Northern," in "A Proud Heritage: A History of Uvalde County, Texas." (Uvalde: El Progreso Club)

S. G. Reed, A History of the Texas Railroads and of Transportation Conditions Under Spain and Mexico and the Republic and the State (Houston: St. Clair Publishing, 1941)

Paul H. Carlson, Texas Woolybacks: The Range Sheep and Goat Industry (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1982)

Ross B. Jenkins, "Cedars and Poverty," The Cattleman, XXVI (June, 1939)

Stuart M. McGregor (ed.), Texas Almanac and State Industrial Guide (Dallas: A. H. Belo Corporation, 1943)

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930 Agriculture (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932), II (Part 2)

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940 Housing (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1943)

Lester Haines, "The Cedar Tap Railroad, the Scholten Brothers Cedar Company, Inc. and the Pfeuffer Cedar Company, 1912–1920," Journal of Texas Shortline Railroads and Transportation, II (Aug.–Oct., 1997)

William M. Marsh and Nina L. Marsh, "Juniper Trees, Soil Loss, and Local Runoff Processes," in Soils, Landforms, Hydrologic Processes, and Land-Use Issues—Glen Rose Limestone Terrains, Barton Creek Watershed, Travis County, Texas, ed. C. M. Woodruff, Jr. and William M. Marsh (Austin: Society of Independent Professional Earth Scientists, Central Texas Chapter, 1992)

Warren M. Pulich, The Golden-Cheeked Warbler: A Bioecological Study (Austin: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 1976).